Following the first sales of crown land in December 1842, St. Kilda rapidly became a fashionable suburb. It was under the jurisdiction of Melbourne Town Council until February 1857 when St. Kilda was proclaimed a separate municipal district. On Saturday, 7th March 1857, 250 residents attended a public meeting in a garden in Acland Street to nominate candidates for the new council. The election was held two days later at a polling booth at the Junction Hotel, and seven councillors were elected.

On 11th March 1857, the first council meeting was held in a public room at the Junction Hotel, at the corner of Barkly Street and High Street (now St. Kilda Road). For lack of other accommodation, most early meetings of municipal councils adjoining Melbourne were held at hotels of good repute. Two weeks later, St. Kilda council meetings were moved to the court house, which occupied a triangular piece of land bounded by Punt Road and St. Kilda Road, directly opposite the Junction Hotel. When a new court house was completed in April1859 at the corner of Barkly and Grey Streets, council's weekly meetings were transferred there also.

Early in 1859, council bought properties so that Carlisle Street could be extended to meet Acland Street and the Esplanade. Some money remained from the amount allocated, so in May 1859 council directed the town surveyor to draw up plans and specifications for a town hall and municipal offices, modest in both size and design, on land next to the court house.

A description, presumably written by the Town Surveyor, tells us that the building was almost square, measuring 63 feet by 58 feet 6 inches. An 1862 engraving shows that the façades were "in the Roman Doric style with Italian windows."

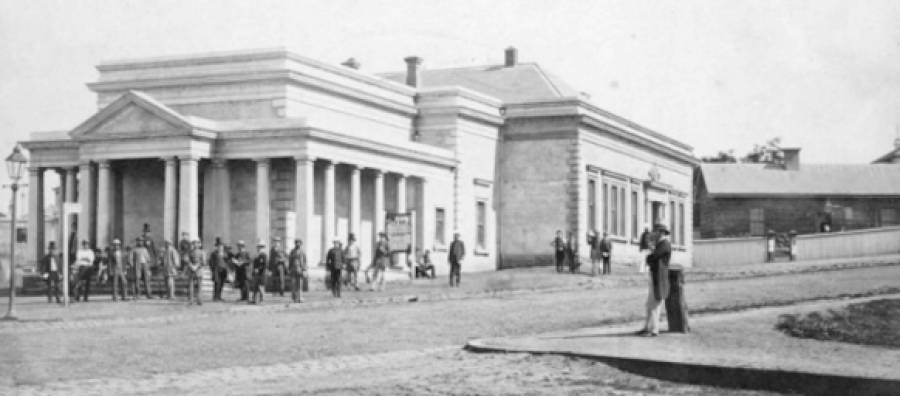

Entrances from both Grey and Barkly Streets led to the council chamber, which extended the whole length of the building. There was a council committee room and rooms for the Town Clerk, the Town Surveyor and the contractors. The foundation stone was laid on 12th July 1859 by the Chairman of the Council, the Honourable Alexander Fraser, MLC. A handsome portico was added to the court house, "with pediment and flight of steps, facing the angle formed by the junction of Grey and Barkly Streets, and on either side of the portico is a colonnade of pillars in the Roman Doric style."

The impressive council chamber, with Roman Doric cornices and pilasters and a splendid ceiling rose, was designed so that it could also be used for public meetings, balls, etc. The first function, on 19th December 1859, was an inaugural lecture to the recently established St. Kilda Mechanics' Institute. St. Kilda council met in its handsome town hall for the first time on 4th January 1860. From 1860 to 1890, while the building was used by council, the shape of St. Kilda was set – streets were made, public transport routes established, churches, schools, shops and hotels erected, and the greater part of St. Kilda's housing built with the exception of Elwood, which was still a swamp.

Within a few years, it was obvious that the building was too small, but it was not until 1887 that the site of the present town hall was accepted and loan funds made available. A design by William Pitt was selected, which included a tower with a richly decorated pediment, a clock and a spire. On 23rd June 1890, St. Kilda council met for the first time in the new town hall, which had been completed minus clock and spire.

The old building in Grey Street was sold to the Victorian government on 29th September 1890. It was used as a court house and police station until 1930, when new police buildings were erected in Chapel Street. For a few months, the old building stood abandoned and derelict; it was then sold and replaced by the present block of flats.

Source:

Cooper, John Butler, The History of St. Kilda 1840 to 1930; Vol.I pp60-93; Vol.II pp39-64.

Courthouse and Town Hall, Barkly Street [ca. 1860], photographer unknown,

Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria

Copyright © St Kilda Historical Society Inc. 2012

https://www.stkildahistory.org.au/

South Melbourne, between the south bank of the Yarra River and Port Phillip Bay, originated at the area known as Emerald Hill, 2 km. south of Melbourne. Emerald Hill, an old volcanic outcrop, stood out from the surrounding swamp land and had greener vegetation. Its elevation above the Yarra delta attracted the initial settlement. During summer, the swamp land dried out and it could be used for recreation or military training. Settlement south of the Yarra River was focused on Sandridge (Port Melbourne), which was linked to Melbourne by a track from a pier at Sandridge beach. Land sales in South Melbourne were few during the 1840s, but in 1852 a survey of Emerald Hill resulted in the auction of subdivided lots. Settlement happened quickly and within two years its residents were complaining that the Melbourne City Council was not giving them value for their rates. On 26 May, 1855, Emerald Hill was proclaimed a separate borough.

At the time of the survey of Emerald Hill in 1852 a temporary township was created west of St. Kilda Road, south of the river. It was Canvastown, a low-lying area with tent accommodation for gold-field immigrants. It lasted for two years and gave its name to the first school (1853) in the area at the corner of Clarendon and Banks Street. Slightly later in Emerald Hill, church primary schools were opened: Presbyterian (1854), Catholic (1854), Anglican (1856) and the Orphanages, Protestant (1856) and Catholic (1857). A mechanics’ institute was opened in 1857. The opening of the Melbourne to Hobsons Bay railway in 1854 did not benefit Emerald Hill very much because it skirted the area, but the Melbourne to St. Kilda line (1857) had an Emerald Hill station by 1858.

The land around Emerald Hill remained unsuitable for housing or industry until it could be drained. The Victoria Barracks, on higher land in St. Kilda Road, was built in 1859, and the military freely roamed the area: rifle butts were in Albert Park and a shore battery was at the end of Kerford Road. In 1863 massive floods inundated the surrounding area and the few optimistic infant industries. Although flood mitigation did not gain a significant boost until the Coode Canal (1887), land reclamation, drainage and river embankment works encouraged settlement on the flat area. The Albert Park lagoon was excavated to form a lake for boat jaunts in 1875.

On 1 March, 1872, Emerald Hill was proclaimed a town which led to the council moving its town hall from Cecil Street to the site occupied by the Protestant Orphan Asylum. State schools replaced church schools: the Eastern Road school (1877), the Dorcas Street school (1881), the City Road school (1884) and Montague (1889), all grew to become crowded, as the population of South Melbourne more than doubled in twenty years, reaching nearly 42,000 in 1891. Before trams came to South Melbourne, Clarendon Street emerged with a main retail strip.

Industries along the river had been mainly noxious, imparting unpleasantness to the growing residential areas. The Harbor Trust (1877) forced the industries to move downstream, and manufacturing replaced them, drawn by the better access across the Falls (Queens Street) Bridge and the construction of South Wharf.

Football clubs were formed in the 1870s and in 1879 the South Melbourne club with red and white colours took its place in the Victorian Football Association. It was one of the founding clubs of the Victorian Football League in 1897. Emerald Hill town changed to South Melbourne on 25 September, 1883.

Tram lines along Clarendon Street and Park Street were opened in 1890, along with the connection made to the city seven years before with a steam ferry between Clarendon and Spencer Street. Manufacturing and food-processing industries expanded back from the riverside. The giant red brick Tea House building, originally a stationer’s warehouse (1890), is a surviving example in Clarendon Street. Notable food processors were Hoadley’s Chocolates (later Allens Sweets) and Sennits ice-cream. Textile mills, timber merchants and furniture trades set up in the 1880s. Clarendon Street, in addition to having many food and drapery retailers, had furniture retailers. Maples, Tyes and Andersons began in South Melbourne and grew to become metropolitan chains. Crofts grocers also began in South Melbourne.

Education broadened to secondary level with a technical school (1919-92), St. Joseph’s technical school (1924-88) and the conversion of the City Road primary school to the Domestic Arts School (1930). Another was the transfer of the Melbourne Girls’ High School to MacRobertson Girls’ High School, in a corner of Albert Park, in 1934.

From Emerald Hill’s beginning with the Orphan asylums, welfare has had strong community support in South Melbourne. The Montague kindergarten opened in 1909, along with Methodist and Catholic kindergartens within a few years. Baby welfare and child hygiene centre were opened during the 1920s. When a South Melbourne local, Harold Alexander, was appointed Town Clerk in 1936, the council deepened its interest in welfare activities. The charitable community-chest and increased rates from commercial properties help to fund welfare activities. At that time South Melbourne was receiving the first postwar migrants, who increased in the nest two decades. Cricket and football was played beside the South Melbourne Hellas Soccer Club (1959), and adult migrant English classes were run at the Eastern Road primary school. Riverside industry expanded, and the Montague kindergarten closed in 1959. Montague was disappearing.

South Melbourne has a strip of land on the west side of St. Kilda Road from the river to the end of the Albert Park. Part of it came from severance from the Albert Park reservation in 1875, providing sites for boulevard mansions. Closer to the river there were several institutional land uses: the Homeopathic (later Prince Henry’s) Hospital, 1882, the Immigrants’ Home (1852-1911) and the Victoria Police hospital. On the site which would ultimately be the Arts Centre complex there were the Green Mill, Wirth’s Olympia and (later) the Trocadero and Glaciarium entertainment venues.

In the postwar years Melbourne’s central business district spilled down St. Kilda Road. Land was cheaper and the council encouraged development attracted by the increased rates. In 1944 the State Government agreed with South Melbourne’s council that the Wirth’s circus site should be reserved for a cultural centre. Postwar shortages delayed the project, and the first part of the Art Centre was opened in 1968. As culture officially came to South Melbourne gentrification came to its residential area. The Emerald Hill Precinct is a registered historic area, and inspired conservation initiatives both private and municipal. By 1981 the population was less than half its postwar figure, and local support for the football club had waned. In 1982 the Swans became the Sydney Swans, and the Lake oval lost its main tenant.

The particularly noticeable changes since the 1960s have included high-rise Housing Commission flats (Emerald Hill Court, 1962, and Park Towers, 1969), the Westgate Freeway (1975-95) and the development of Southbank. On a smaller scale there were the conversion of the South Melbourne Gas Works to a park (1982) and the conversion of the Castlemaine Brewery to the Malthouse Theatre (1987).

On 18 November, 1993, the area of South Melbourne defined as Southbank and extending to Docklands was annexed to Melbourne city. On 22 June, 1994, South Melbourne city was united with St. Kilda and Port Melbourne cities to form Port Phillip city.

South Melbourne municipality’s census populations were:

1861: 8,822

1881: 25,374

1891: 41,724

1921: 46,873

1961: 32,528

1991: 17,712

Miss Camm, having arrived in Victoria in August 1854, went

with a party for a picnic to Brighton.

They made the journey in a dray. On their return, the driver of the dray

sought a short cut to St Kilda along the margin of the Elwood Swamp. They were

well into the swamp, with its slimy mud bed, when the horses became

frightened. The men had to carry the

women to the lagoon’s margin where there was firmer land, and in doing so the

men sank into the mud as far as their knees.

From Elwood’s first Settlers by Beverley Broadbent 2005.

The Elwood canal is a unique seam of open space running

through the urban fabric of Elwood. In

its former life it was the Elster Creek, which drained to a swamp near the beach. This rare nineteenth century canal has shaped

Elwood’s pattern of settlement, its parks and public works, recreational spaces

and wildlife habitat. Today the Elwood

Canal Master Plan of Port Phillip Council is guiding its restoration from a

drain to an aesthetic waterway.

For most of the nineteenth century the wetland was viewed as

a barrier to European development. While

the subject of complaint for moist of its history, it has also been a source of

striking recollections, even entering into Australian literature. In his brilliant autobiography, A Fine and

Private Place, Brian Mathews describes an epic voyage as a child up the Elwood

canal from the foreshore to his home.

Leigh Redhead’s crime thriller, Peepshow, culminates in a violent

struggle between female sleuth, Simone Kirsch, and a corrupt cop in the ‘oily

waters’ of the canal. The brutal murder

of Molly Dean in 1930 in a nearby lane off Addison Street was included in one

of Australia’s best-known novels, My Brother Jack by George Johnston.

Today, the Elwood Canal is a man-made watercourse connecting

the lower reaches of the Elster Creek with Port Phillip Bay, three hundred

metres north of Point Ormond. It drains forty square kilometres of southeast

Melbourne, including Prahran, Glen Eira and Kingston. The upper reaches of the creek were

originally a natural watercourse that ended in an ill-defined wetland near the

beach between 108 and 160 acres in size, depending on rainfall.

Swamps like Elwood, which waxed and waned with the weather,

were the natural safety valve of streams and rivers and the source of food and

wildlife for the traditional owners.

However, European settlement changed all that by using waterways for

waste disposal. In 1869 the foul

conditions of the Elwood swamp prompted local residents to call for the St

Kilda Council to remove the nearby abattoir and night soil depot. Added to their problems, the Brighton Council

in the early 1870s cut a drain through Elsternwick Park to near the swamp's

boundary at St Kilda Street. To prevent Elwood flooding, the St Kilda Council

was forced to continue the drain to the Bay, which until 1904 entered the sea

about 150 metres north of the canal's present mouth (near today's Meredith

Street)

Life by the swamp is illustrated by a story told by R.D.

Ireland, a barrister famous for his defense of the Eureka rebels. Ireland and his friends were invited by

Richard Heales, Premier of Victoria, to dinner at Tennyson Villa (1860) in

Tennyson Street. The mansion stood out

like a lighthouse on a ‘forest of piles’ in the middle of the Elwood swamp

which heavy rain had turned into a lake.

Boats conveyed the distinguished guests to the house. Wet and chilled, Ireland bitterly lamented

the lack of alcohol (Heales was a teetotaller) until whisky arrived which was

immediately quaffed. The whisky turned

out to be lemon concentrate, leaving Ireland and his friends choking, inwardly

cursing their host and calling for the boats.

There were physical dangers.

A beachcomber who sold mussels to buy alcohol stumbled into the poorly

lit canal during a storm and drowned, as did journalist Arthur Davies on the

night of 31 July 1898.

By 1888 the Mayor and Health Inspector of St Kilda Council

found the stench from the swamp to be an ‘intolerable nuisance’. 11 Sixty men were employed to construct a

concrete canal 1.2 kilometres from Glenhuntly Road to Elwood beach. Engineer Carlo Catani (1852-1918), was

involved in the design. Mooring rings

were provided on the canal’s walls for typing up pleasure boats. Iron girder bridges, supported on brick

piers, were initially built at Marine Parade, Barkly, Addison and Ruskin

Street, and Broadway.

Most of the water was supposed to be carried out by pipes on

the walls but since they weren’t maintained, all water entered the canal. The canal was also found to ‘float’ and now

has six inches of concrete base to anchor it.

Additional drains such as the brick drain at Byron Street were connected

increasing the overload of water.

Engineer George Higgins was also engaged to drain 134 acres

of swamp on crown land. An additional 26

acres of private swampland near Byron Street was drained and subdivided for

speculation. An advanced dredge built by

Alexey Von Schmidt was imported from San Francisco. Acclaimed by the public as a mechanical

marvel, it was mounted on a barge, pumping sand and clay from the Elwood

foreshore, mixed with water, into the low-lying swamp areas. Surplus water was then channelled back to the

Bay. The canal was also extended from

Glenhuntly Road to beyond St Kilda Street.

By 1905, the St Kilda Council was finally able to report that the swamp

had been filled.

Engineer John Monash, later commander of Australian forces

at Gallipoli and France, built six bridges across the canal between 1905 and

1907 of which two survive. His first

bridge at St Kilda Street is the earliest surviving reinforced concrete girder

bridge in Victoria and possibly Australia.

This innovative design inspired the use of reinforced concrete for

bridge building throughout Victoria. 12

The first sales of residential land allotments on the former

swamp took place on 21 January 1908.

Most of the land adjacent to the canal between Marine Parade and

Broadway was sold in 1914, with those adjacent to the canal upstream of

Broadway not sold until the 1920’s.

In 1924 the Melbourne Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW)

assumed responsibility. They proposed in

1928 to fill in the entire canal to create ‘rateable’ land but were deterred by

the Great Depression.

A polio epidemic in 1937-8 caused many panicked parents to

label the canal as Plague Canal and ban their children from the vicinity,

including the local school which in 1937 closed from June to September. The MMBW reacted by widening the upper reaches

of Elster Creek to improve the flow.

Violent storms showed the canal was ineffective in

preventing Elwood from flooding. A

record high tide, combined with gales of 100 kpm per hour in December 1934,

caused the canal to break its banks, extensively damaging a number of

homes. The following year saw flooding

close Marine Parade in April and Foam Street inundated in May. In November, waves beat on the sea wall,

furniture floated in homes and boys delivered papers from rowing boats. In 1955, after another serious flood, a

project began on a giant diversion drain beginning at New Street, Brighton, and

emptying into the Bay at Head Street to dramatically reduce the flow of water

in heavy rain. The dumping of rubbish in

waterway and on the banks by local residents was also of continued annoyance.

By the 1960s, the canal had begun to improve with re-grading

of banks, planting of lawns and renewing access roads, right-of-ways and

footpaths. Two new bridges, for north

and south-bound traffic on Marine Parade were constructed across the canal in 1967. These were made possible by the reclaiming of

45 acres of land from the sea, 25 acres of which were set aside for

recreation. The remaining 20 acres were

allocated for the new St Kilda Marina built in 1969. in 1972 the mouth of the canal, downstream

from Marine Parade, was widened and its banks lined with rocks and the adjacent

land gazetted as a recreation reserve.

In April 1970, more attention was drawn to the outlet when

Prince Charles swam at Elwood and described the water as ‘diluted sewage’. In the same year the MMBW was appointed as

the Committee of Management of the land surrounding the canal between Marine

Parade and Goldsmith Street. From 1983

onwards, demands from local residents and the council saw it developed as a

linear park to encourage recreation with bike and pedestrian paths connecting

to the beach.

The environmental group, Earthcare St Kilda, and local

residents agitated for change and undertook plantings with St Kilda Council

staff. An Elwood Canal Task Force was

established in 1993 from the local community, Melbourne Water and the City of

St Kilda, resulting in further works to improve the flow of the canal and the

condition of its environs. Flood

prevention works have also been undertaken, including the construction of lakes

in Elsternwick Park to help with water management. Landscaping along the canal

and its mouth at Elwood beach, including the construction of the John Cribbes

footbridge in 1998, have transformed the water feature into a centre for

recreational activities.

Today this open canal remains a unique Melbourne landscape

and an integral part of the urban character and history of Elwood.

The removal of the swamp was one of the last barriers to

improving Elwood's prosperity. The other barriers were the noxious activities

which had plagued the suburb for most of the 19th century.

Elwood Swamp 1886. The bisecting roads are Barkly Street and

Glenhuntly Road

(Map Collection, State Library of Victoria)

Credit: St Kilda Historic Society https://www.stkildahistory.org.au/

Original article: http://skhs.org.au/~SKHSflood/From_Swamp_To_Canal.htm

Picture: Elwood Swamp 1886. The bisecting roads are Barkly Street and Glenhuntly Road(Map Collection, State Library of Victoria)